Lisa Pinhas

Lisa Pinhas, a Greek Jew from Thessaloniki, vividly recounts her experiences in the concentration and extermination camps.

Lisa Pinhas was one of the first women survivors in Greece who, in the fifties, decided to put her overwhelming experiences from Auschwitz-Birkenau on paper. For Lisa, this was a totally conscious decision given her understanding that until then only men had published their testimonies concerning their deportation to and confinement in Nazi concentration camps, whereas women's stories remained unknown. In her book, not only does she unfold her own story but also the tragic fate of her community, the Jews of Thessaloniki, the largest Sephardic community in Greece and the Balkans. We've gathered excerpts from her book that illuminate her hardships from the very day when German troops entered Thessaloniki, until the day when she was liberated.

The entrapment of the Jews of Thessaloniki

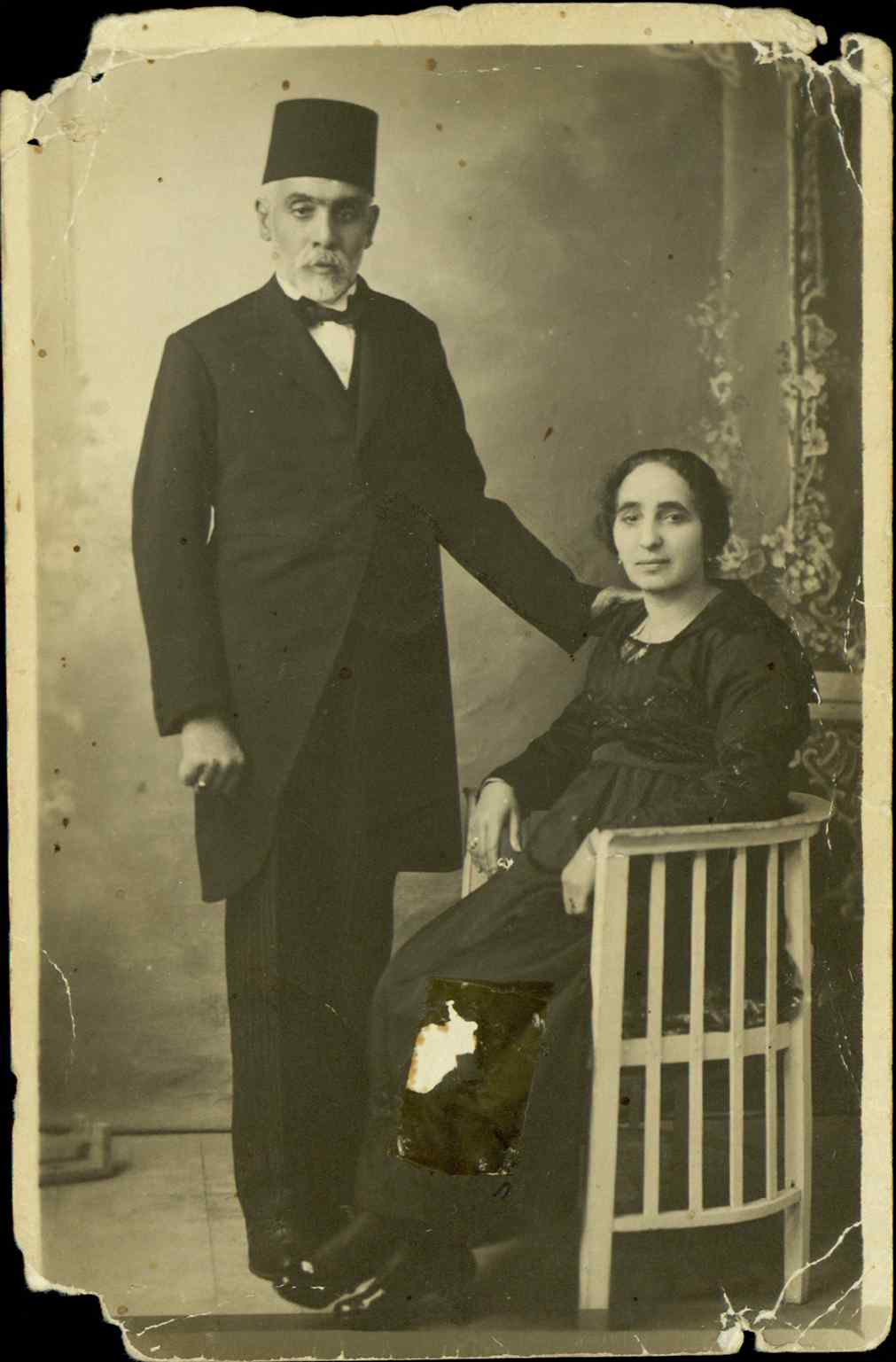

Lisa Pinhas' parents, Yeshuah Joseph and Mazaltov Mano @JMG Collection

On April 9th, 1941, when the German troops occupied our country, we were far from imagining the infernal programme which had already been prepared for us. For one whole year, they worked on putting our minds at ease, and all of a sudden, on their order, the press started writing evil articles, spitting the most pernicious venom about us.

…

On July 11th 1942, a press release was published in Greek in the newspaper “Apogevmatini” (Matinée) which ordered that all Jews aged between 18 and 45 present themselves at 8 o’clock in the morning in front of Eleftherias Square.

They spared us no humiliation, offending and insulting us, and no one dared to react, being too afraid of being immediately executed. The feeling of this sudden change from a harmonious and pleasant life to this unexpected system is literally impossible to describe. It was an enormous shock for us. Mentioning our state of mind would be unnecessary; you can easily imagine: brutally pulled away from our homes, deprived of everything in just a few minutes.

…

The turn of my family came. This is how it happened: we felt the danger coming closer and we were making escape plans at dawn on March 31st [1943] when we were suddenly woken up by repeated whistling, then it was too late. We were trapped. That dawn will remain forever so vivid in our memories; remembering still hurts us, removing all happiness and smiles. All we could feel was emptiness, just the cold emptiness of so many beloved people, whose loss we will never mourn enough.

Entering Birkenau

The train suddenly stopped at 2:30 am. Through the diabolic light that shone on us, our eyes were surprised by the unexpected setting that unfolded in front of us. It was Auschwitz, the station of death. A meticulous selection was made, and we were forced to stand in rows of five: that was the system in this camp. Fifty women all in all stayed from the same transport; we had been deemed suitable for the functions of the camp. They made us go, accompanied by sentries, five by five, with a military walk. After a 20-minute walk, we saw strong lights and guards perched in a variety of places. A gate opened when we arrived: it was Birkenau camp.

…

A strict control took place that stripped us of everything. They took our handbags, our jewellery and even our wedding rings; they went through our pockets and took everything out, even our handkerchiefs. Early in the morning, we had to pass, in alphabetical order, to be tattooed. It was sore, but that was nothing in comparison to what awaited us. From that moment on, our name was replaced by a number on our left arm. We had changed character; we were branded like cattle, we were Häftlinge [inmates], I was called 41117.

…

In one morning roll call, we stayed motionless for hours. Who would dare do the slightest movement? In front of each block, 800/1000 prisoners were lined up and one after the other, like bothersome and annoying flies, passed and counted. The evening roll call (Appell), taken on our way back from work, usually didn’t last more than an hour in any weather.

…

The blocks were big barracks used as dormitories. They would be very much like stables if it weren’t for the rows of racks that were supposed to be beds. Imagine these ten persons lying on one side, the same way, packed like sardines, without being able to move or breathe, with their feet pulled together because two persons slept on the end of the bed in the opposite direction. Lice, flees and all sorts of parasites proliferated. They were biting us, but we couldn’t scratch ourselves because we literally couldn’t move. They quietly sucked our blood undisturbed. We used these beds for anything. This is where we took our meals.

…

At lunchtime, we got a small cup of a weird liquid called “soup”. Yes, it was a disgusting and unhealthy broth, which contained anything from thistles to insects or pieces of rotten bread. Sometimes there was potato soup, made from rotten leftover potatoes or even potato skins, with muddy carrots because they weren’t even washed. I forgot to mention that in order to make these soups tastier, they always added a certain dose of bromide, which made them even more repulsive.

Struggling to stay alive

In order to live, we had to find another way. Some had a man “kochanie”[a sympathy or a friend] and always had something to eat; they regularly received “Kanadas” [packets]. Some of these “kochanie” held high positions, which was clever as they didn’t let them lack in anything, so to speak. They always found ways to corrupt the German guard who could be bought for a few German marks, in order to go into the women’s camp as workers for a few hours. Of course, the women, when they could, would do the same favours for men, too.

…

That’s when I met Zeili Pat, a young Pole, who was a sincerely good friend to me. He was very considerate and “organised” continuously to bring me rare things: a small tomato (there weren’t any), sugar, soap, etc. He was the one who advised me to talk to the Meister to make him change my tasks.

…

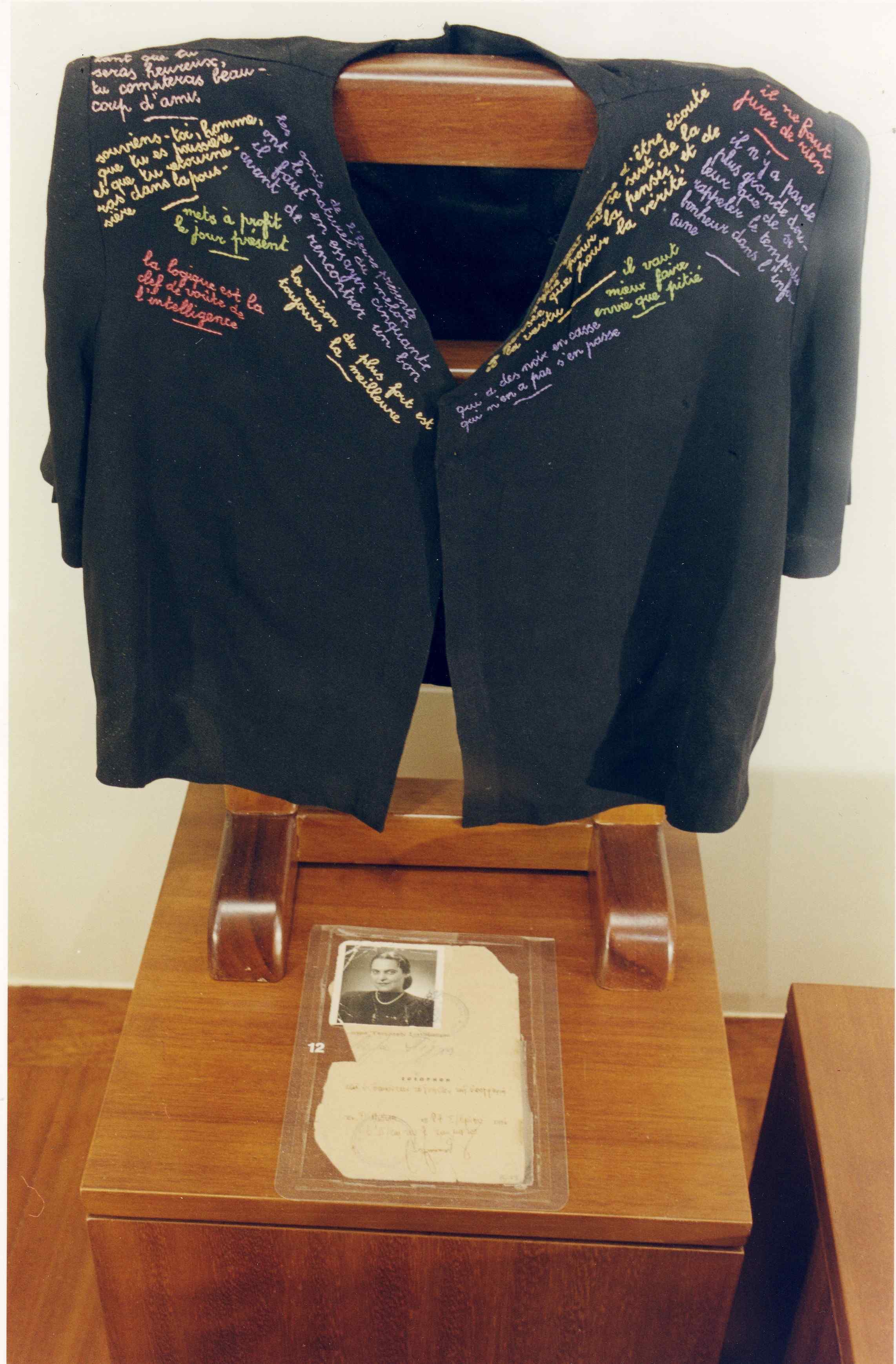

Lisa’s younger sister Marie, like many Jewish survivors, immigrated with her second husband to USA in 1951. Under her sister’s pressure, Lisa migrated to the United States in 1952, but she returned in 1954. @ JMG Collection

My younger sister spent two months in the hospital. She was the only sacred thing that I had left of our whole family, that kept me alive. I was afraid for her, checking on her poor health, without her noticing. She was indeed my pride and joy.

…

Four young Jewish girls who worked in the Union-Werke factory were caught. They were accused of having regularly provided hand grenades and explosives to the camp and to the group who revolted at the Sonderkommando. A surprise awaited us. As we entered the camp, we noticed that two gallows had been built at the back of the Lagerstrasse. The Germans forced us to watch it to the end.

…

The threat of death was continuously hovering over us, despite our desperate efforts to survive. There were Selektionen each week. We lived day and night with this fear. The crematorium and its high chimney seemed to be waiting for us; we were dying slowly. For most of us, it was on the way back from work, unexpectedly, that we were to go through “Selektion”.

…

So, in order to escape death, each one of us was also “organised”, in our own way.

…

I had met a young Polish woman called Hanka. She worked in the kitchen. She was a knowledgeable and intellectual young woman. We got along very well and soon a very strong friendship bound us together. My friends Bella, Mini, my younger sister and myself would bring her very valuable jewellery, money, nice clothes, fine stockings, perfumed soap and other things every day.

…

I worked the land for a whole month, which felt endless. We didn’t have a change of clothes for that whole time.

…

The Schreiberin [clerk] slowly looked at me; she seemed to like me and she immediately wrote down my name and number in a notebook along with other names. “You fool”, she said as she smiled, “what are you afraid of? Going to a rich Kommando where you can “organise” whatever you want? I know some others who would like to be in your shoes”.

On the brink of death

At the break of dawn, we left the camp in columns, miserable processions of starving slaves, skinny, hopeless, in order to work with shovels, pickaxes and demolish houses, clean up ruins, construct roads and railways, load and unload wagons. We were continuously insulted and beaten with sadistic pleasure on our way to work. In the evening on our way back, we often had to carry one or two comrades that died of exhaustion or of a heart attack and we had to walk along with the rhythm of the music.

…

I was very worried for my sister and my niece. I thought my sister, whom I was about to lose one month earlier, was luckily out of danger, but she had huge spots on her hands and she was worried. Every evening, I “organised” some nice soap and new towels. I bribed the nurses at any price, so that she had water to be able to get washed.

…

A new transport from Thessaloniki arrived; one could tell from the baggage that was brought to the “Kanada”. As I walked into my block, I found out that my father, my mother and my sister were in the same transport. They hadn’t entered the camp. This was a terrible shock for me. I am still wondering how I managed to survive that pain. No pen can describe the whole dimension of this horror, the details which today might sound vulgar, but at that time, they were very important to us.

…

I had inflammation on my leg. For more than one week I had a 40-degree fever but didn’t tell the Pflegerin [nurse] who would certainly have sent me to the Revier. I had to stay at the block, in other words in front of the block, on the ground from the morning to the evening, with others who hadn’t been well, for more than two months.

Usually, since I stayed at the block, I went to wash my wound and my bandage very often during the day when the Waschraum [bathroom] was free. One day, I saw two Kapos (Poles) who were washing themselves. When they saw my wound they called me schwein, dreck [pig, rabbish] and who knows what else. They threw themselves on me like two bulls and beat me with an incredible and savage cruelty. Despite the pain I felt, I defended myself. It wasn’t long before I fell unconscious on the floor, in a pool of blood.

Lisa Pinhas during her visit to Auschwitz, as head of the Greek survivors' delegation. Lisa believed in the importance of preserving the memory of Holocaust victims as an antidote to oblivion. (ca 1960s) © JMG Collection

The last months

I was still in Barrack no.3 where we worked non-stop making packets with the clothes of the deported Jews for Germany’s profit. All around me were foreigners who spoke Slovakian, Polish, Dutch etc. but especially German. In this tower of Babel, we nearly even forgot our mother tongue. I was separated from my Greek friends, but I was lucky enough to have a young French woman working at my table. She was witty and charming; her name was Liliane. I became her good friend very quickly.

…

It was already May (1944), and the transports from Hungary started to arrive. The transports carried on arriving at a very quick pace. Very soon, the camp could no longer host so many people at the same time despite the fact that we were more squashed than usual. Who knows how many of these transports ended up in other crematoria? They were lacking every comfort: instead of clothes, they were given dirty old and holed blankets to wear as clothes. They weren’t women anymore, they were poor ghosts, gaunt, skinny, and more like animals. Everything in the Kanada was full; we walked on these abandoned things, we ate non-stop, even when we weren’t hungry, because at that time we weren’t hungry anymore. Sometime after, the transports had become less frequent, the work in the Kanada was less important. The Russians advanced.

…

Between the factory [Union-Werke] and the block, our days were uniformly sad and hard; we fought constantly for life, to save ourselves. When the bombing was more intense, we looked for a more secure shelter. It was the end of 1944.

The hope of liberation and the death march

The great day finally arrived. The night of January 17th, 1945 was very busy. The Aufstehen [morning roll-call] that morning was very different from other days. Everyone was in a hurry to leave the block. We were convinced that a general roll call would take place for an immediate transport.

…

Goodbye forever, awful Auschwitz, land of torture. The Selektionen were over for us, so were the crematoria. This life of humiliation and nightmare was over for us. We could accept anything after this awful hell. Escorted by the SS Posten [guards], we left Auschwitz for an unknown destination. On the naked and deserted road that was covered in snow, we walked at a fast pace at the beginning. We stopped; the Germans wanted to find the direction. Far away, in the night, the sky looked like a huge brazier.

…

Towards the evening, we arrived near a railway. There was no station, but we discovered we were in Prenzlau. It was a terrible journey; we all had fever. When we arrived, we were only ghosts. In the morning, towards seven, we were taken outside for a roll call. We were also curious to know where we were. It was Ravensbruck.

…

It was still daylight when we were put on trucks. The journey was very long and tiring. We were relieved when we saw the truck stop at last. It was Rechlin.

Despite my precautions, I was unable to escape from the plague of diarrhoea. Bella, Mina and my sister Marie regularly came to see me in the evening, they brought me pieces of leek in order to save me from death. They had thought of everything, arranged everything to save me.

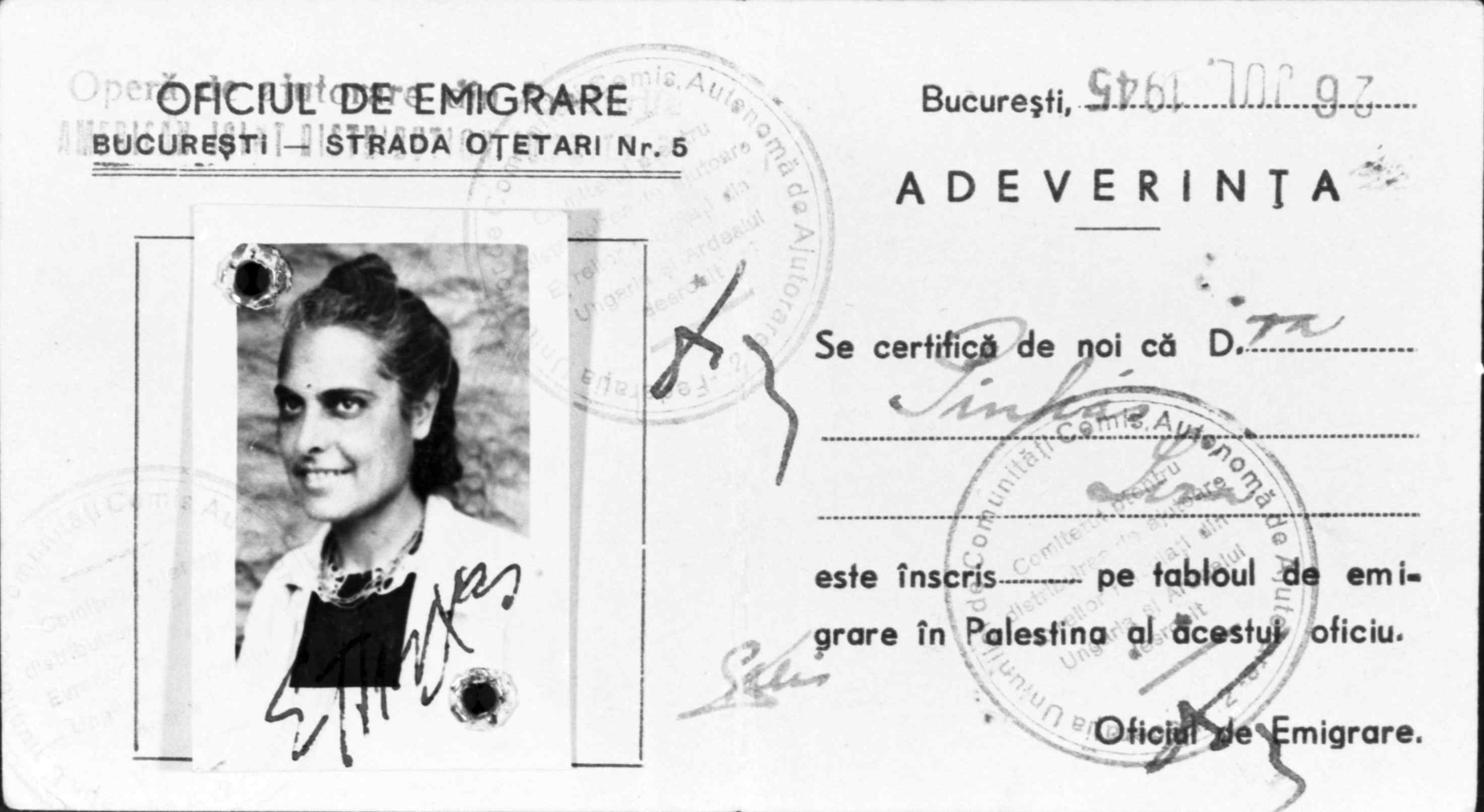

After her release, in her attempt to build a new life, Lisa was issued an immigration permit in Bucharest in 1945 to emigrate to British Mandate Palestine. In the end, she never made use of this permit and returned to Athens. ©JMG Collection

Finally, free!

On the evening of April 26th, the Blockälteste told me that the Greeks and the Hungarians had been requested by the Red Cross and that we would have to leave the camp the next day. April 27th, 1945; this is an unforgettable date. All the Greeks walked in one separate group.

This was a moment of indescribable joy; it was madness. We cried, kissed, danced and laughed through the tears like mad. We were free! Free! At last. For us, this word was filled with bitterness. Our soul was hiding a tragedy.